Myths, Facts, Lies, and Humor About William James Sidis - Part Two

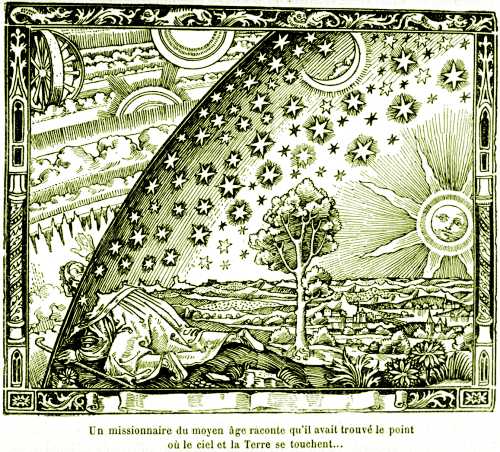

(PD) Cammille Flammarion - Flat Earth

Copyright ©2008-2021 — updated February 11, 2021

The following condensed topics are taken from my personal unedited notes, written under the working title of Myths, Facts, and Lies About Prodigies, and from a chapter that lists fifty popular online claims about William Sidis. Each topic's comments have purposefully omitted lengthy detailed information that will not be made public. The purpose of the following comments is to present concepts that question the popular belief that William James Sidis was the smartest man on earth.

The unexpanded notes on topic #1 alone consume about 8,500 words, but I will be kindly brief.

1: At about six months old, William Sidis' first word was "door."

"It is common for children of average intelligence to speak their first word at about six months old or younger, and so the claim about William speaking a word at about six months old has no immediate relevance to prodigious talents nor to the claims that William was the smartest man on earth. However, since an individual's first word does help indicate what the child is giving above average attention to, and thus how the child's mental structuring is developing, it is useful to further investigate the more important aspects of the topic...

It is also significant that William's first word would be "door" instead of "mama" or "dada." A child's first word is a strong clue as to what type of environment the child is being raised in, as well as what type of mental and personality preferences the child is developing. As a quick side-note, my child's first word at about five months old was "love," which I feel speaks for itself. ...William's interest in doors may have been an indication that he had a strong desire for social interaction (people entering doors)."

Sarah Sidis, William's mother, in The Sidis Story, is the one that wrote of William's first word, and thus the claim is likely true or close to true. The most important item to recognize in William Sidis' first word is his age of six months. At an age that other children have already begun talking, and some children are learning English as their fourth or fifth language, Sidis' language skills were common, and not of a superior level. Sidis' age of speaking his first word does not support the belief that he was the smartest man on earth.

2: At about seven months old he spoke the word "moon."

"The claim does not include information about what other words may or may not have been said. The claim leads the reader to assume whatsoever the reader wishes to be true relative to the reader's own mood and personality. Did Sidis not learn any other words between "door" and "moon?" Had Sidis only learned two words in seven months, which would imply a slow learning curve?

...Sarah wrote in The Sidis Story: "The first thing my April Fool's boy wanted from the great outside world was the moon. We stood at the window of the apartment together in the evening, with Billy in Boris' arms, and admired the moon over Central Park. Billy chuckled and reached for it. The next night when he found that the moon was not in the same place, he seemed disturbed. Trips to the window became a nightly ritual, and he was always pleased when he could see the "moo-n.""

The story of Sidis' sensorial unawareness of his environment lends evidence that his was not a superior intellect (or at least not as a toddler). Stories of Sidis' lack of eye-hand coordination as a youth, and as an adult, lend to support a hypothesis that Sidis' perception was not out of the ordinary.

3: At about 1 year old, he learned to spell.

"Spell what? How many words? How big of words? Without the additional information, a person who dislikes William can invent negative interpretations, and the person who likes William can invent fantasies of prodigious talents, but neither of the interpretations are based on evidence. It is wrong always for anyone to believe anything without sufficient evidence."

4: At 18 months old he read a newspaper.

"How well? Every word? Understood every word? The claim does not provide sufficient information to form a logical concept of William's talents. Another claim says William was reading English by the age of two.

The learning of how to read is a gradual process that requires a length of time to develop. Learning to read progresses from being able to read a little to the stage of being able to read a lot. In no stretch of the imagination can a person magically begin reading or understanding all words at a specific point in time, and when claim number three is weighed for logical balance with claim number four, then if William could spell at twelve months old then he should have been able to read as well. True? The claims conflict with the other, creating an illogical balance of information, and there is not a sufficient quantity of verifiable information to base a conclusion on.

Common metaphors used by adults cannot be understood by a child until the child has sufficient life experience to comprehend what the metaphors imply. "Green with envy" is an example of a term that cannot be understood by any human until the individual has lived long enough to have experienced envy plus how words of colors are used to imply varying degrees of intensity. Regardless of how intelligent any human might be, and regardless of any claim, personal firsthand sensorial experience always has been and always will be the controlling factor of what the intelligence can and cannot understand. There is bodily sensorial perception, followed by mental cognition of the perception, followed by memory storage of perception information, followed by mental association of memory, followed by the weighing of association (logic), and then followed by reasoning (which is cumulative logic). The capacities for memory, logical association, and reasoning exist even if there is no sensorial cognition, but neither the logic nor the reasoning can produce accurate results about an object if the object is not sensorially perceived. Without the firsthand experience of sensorial perception of an object, the logic must rely on memories of other similar objects, which forces the logic to be based upon inaccurate generalities at best, beliefs and fantasies at worst.

By eighteen months old William may have experienced degrees of envy in himself or others, and he may have understood some metaphors, but since his writings later in life give evidence that he did not understand many words at the time of the writings, then it is likely not possible for him at eighteen months old to have personally understood all the implications of all phrases in a typical newspaper. It is reported that at fourteen years old William said he had never read the Bible, and if the report is true, and since newspapers frequently reference Biblical topics, then it was not possible for William to have read and understood newspapers.

The claim of William's ability to read at eighteen months old helps lend a small bit of information that William, as also the general population, was learning the language of words without well understanding the words, and the information is useful when compared to how William used similarly non-understood words later in life. William's environment was predominately the memorizing and working with academic topics, the act of thinking without the associated act of sensorially validating the thoughts, and no inference should be suggested otherwise."

A known child, who was not taught to read, but learned on her own, was reading billboard signs by the age of two. Considering that Sidis was taught from the womb to read, his age of learning to read was not remarkable.

5: At 3 he learned to type.

"For a person who reportedly could already read by the age of eighteen months, does this imply that it took him another eighteen months to learn how to depress a mechanical key? Did he type forty words a minute, or did he hen-peck? Many children today learn to use keyboards and computers by the age of two... without additional information William's use of a typewriter at three years old is not relevant to an individual's intelligence.

Boris was quoted in a newspaper article as having stated "When he learned that he could express himself more quickly and clearly on the typewriter than in handwriting, his natural eagerness led him to master the typewriter." By having the small additional information that William discovered typing was faster than handwriting, claim number three now has a degree of usefulness and relevance.

...the most useful relevance of the reports is that they show William's early interest was in communication through languages."

6: At 4 he taught himself Greek and Latin, and he read a book in Latin and a book in Greek.

"How well did he learn the languages? How well did he read the books? Did he read all the words? All the books? Did he understand the words? Again, the claim does not provide sufficient information to form a logical concept of William's talents.

In The Sidis Story Sarah wrote: "Billy was a little slow in learning to talk, so we were surprised when he learned Latin and Greek when he was three." According to Sarah, claim number six is incorrect.

In The Prodigy it is reported: "Boris taught his three-year-old the Greek alphabet. Then, with the aid of a Greek primer, Billy taught himself to read Homer." Claim number six allowed the false belief to exist that William taught himself Greek without help, and again the claim is found to not agree with many other reports."

As mentioned previously, some children are beginning their fourth and fifth language by six months of age, and Sidis' skills with language are not sufficient to support the 'world's greatest child prodigy' myth. Other children, raised in an environment where Greek and Latin are spoken, learn the languages by the age of twelve to twenty four months. It may be uncommon for a toddler in the USA to learn multiple languages, but Sidis' talents as a young child were not extraordinary.

7: Between 4 to 8 he wrote four books (which are now lost).

"Many children at that age write books too. What sort of books were written? What type of words were used? Were the words spelled correctly? Were the sentence structures correct? How large or small were the books? The claim does not provide sufficient information to form a logical concept of William's talents.

When comparing William's writings throughout life, the majority were of relatively few words, typically no larger than a common article. It is observable that individuals with wide mental patterns and who are well experienced in a topic will typically write at length on the topic, and that individuals who have narrow mental patterns and have little experience in a topic will typically only write a few short sentences. It is easily observable which individuals are 'academic ten words or less' memorizers, and which individuals have high intellectual potential."

8: At 6 he learned Aristotelian logic.

"How well did he learn it? Did he understand Aristotelian logic or did he just memorize the words? (Aristotelian logic is generally expressible upon the algebraic-like syllogism and mental structuring of "If all X are Y, and all Z are Y, then X and Z are the same.")

Billions of people memorize information about topics without the people ever understanding the topics. Other prodigies fully understood the principles (and flaws) of Aristotelian logic before six months of age. Some prodigies had a good working concept of the Aristotelian type of logic at two days old. Claim number eight may perhaps indicate an above average intellect, but it does not support the claims of William having been the smartest person on earth."

9: At 6 he learned Russian, German, French, and Hebrew; he later learned Armenian and Turkish.

"Many children of average intelligence at six years old or younger memorize phrases of different languages, and the children are able to lightly converse with people in the languages. No information is given about how well William learned the languages, and therefore the claim has little significance beyond William's interest in the symbolism of languages. According to the information gleaned from his records, William did have quite excellent use of the languages, but the claim by itself, without additional information, requires belief."

10: At age 6 he could calculate what day of the week any date in history would fall on.

"The child who has a special interest in a subject will naturally excel in the subject early in life. While the ability to calculate dates does show an above average talent, and the ability does show evidence of William possibly being capable of mentally recognizing rhythmic patterns, even if mathematically derived, still the talent by itself is insufficient to warrant labeling the child a prodigy.

Page 25 of The Prodigy states: "When Billy was six, Boris gave his boy several calendars and explained them in detail." Page 43 states: "When he was five, Billy had devised his method for instantly calculating the day of the week on which any given date, past or future, would fall." Contradictions of data are too common throughout The Prodigy.

Boris reported... "I taught him to count with similar blocks, and then, wishing to familiarize him with ideas of time, as well as the meaning and use of numbers, I placed in his hands several calendars and taught him their use. At five from his own studies of these he had devised a method of telling on what day of the week any given date would fall." (The Child Prodigy of Harvard by Boris Sidis.)

While the numerous contradictions of ages and events are not always overly important in of themselves, it is very important to realize that no references about William can be fully trusted as fact.

...Although it cannot be known how well William grasped the element of time, it is considerably less than prodigious that a child would be five years old before giving conscious recognition to time, days, weeks, and months.

...William's First Book on Calendars, allegedly written at five years old, is reported in The Prodigy that he stated "Without the sun there would be no such thing as a season." To have only commented on the sun, without including the many cyclic variables of temperatures, dualities, life, and all else, it is my opinion that the alleged book provides further evidence that William was not well aware of his sensorial perceptions, nor what a season is. William's book is said to have included time zones, seasons, leap years, lunar phases, and so on. While it is interesting to see a five year old child write such a book, there is a glaring omission within the book, an omission that almost all other books are guilty of too, and that is...

The Prodigy reports that Boris later built a small lab where William made thermometers and recorded daily meteorological observations. No known report of William gives evidence of his having had any useful quantity of sensory recognition, and it is upon such a lack of firsthand self-observation that his mental abilities were structured.

...An excellent example of the differences between minds structured upon language and minds structured upon life: "At the end of the Moon of Falling Leaves..." (Black Elk Speaks as told through John G. Neihardt (Flaming Rainbow) by Nicholas Black Elk.) In the example, the native American language uses fluid references to what is real, what is in motion, what is in change, what is manifesting and being manifested, to what is sensorially perceived, what is mutually shared objectively among the individuals, and is unmistakable in its references to Reality. The English term "October" is dry, empty, static, a mechanized dissection of Nature, a Darwinian segmentation of illusory time, a subjective symbol that can (and most often is) used without an understanding of what the symbol refers to. Words can change, October can become Wednesday, but Reality remains unchanged. Symbolism is not the thing itself, and a language not based upon perceived Reality is an empty language. Many people claim empirical observation is necessary for principles of science, but people deny that empirical observation is necessary for principles of life.

To myself, the idea of William having to be taught the meaning and use of calendars is indicative of mental dullness and a serious lack of conscious perception of one's environment, but such is my personal interpretation, one that is most assuredly not shared by everyone."