ETHICS - Applied Ethics

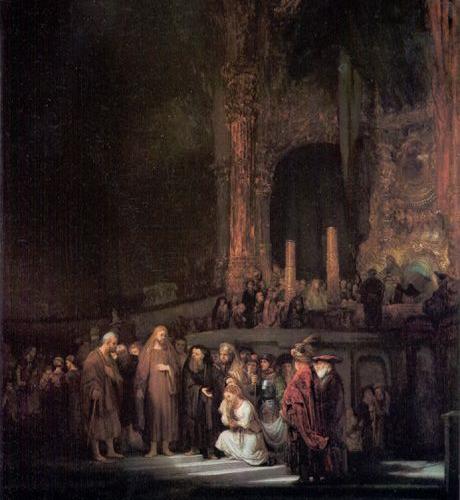

(PD) Rembrandt Woman Taken in Adultery

Copyright ©2009-2021 - updated February 15, 2021

"Genius is the ability to act rightly without precedent - the power to do the right thing the first time." - Elbert Hubbard

A brief definition of Applied Ethics: "(1) A classification within western philosophy. (2) The philosophical search (within western philosophy) for right and wrong within controversial scenarios."

Part One

As a little background, and as discussed on the Christian Ethics page, it is normal for humans to place memories into mental classifications and to then give the classifications a name. The classification "animals" will include within it the person's knowledge of animals, and the classification "ethics" will likely include within it the person's thoughts of right and wrong behaviors. It is also common for humans to subdivide the classifications into smaller classifications with each receiving its own name. As an example, the classification of animals might be divided into classifications of (1) mammals, (2) four legged mammals, (3) two legged mammals, and so on. The sub-categories within classifications are often the result of the individual having a sizable quantity of knowledge about the topic. As another example, the majority of people might have a classification for electricity that only has within it the knowledge that electricity exists, that electricity powers appliances, that electricity can shock you, that electricity is taught to be electron flow, and that electricity is synonymous to the word "voltage". Another individual, however, who has more education of electricity may have created numerous sub-categories within the main classification, with the sub-categories being of amperage, ohm's law, resistance, electromagnetic flux, and so on. Nevertheless, another person with an even greater knowledge of electricity may simply have the classification divided into two segments: (1) educational knowledge and (2) dimensional potential.

It appears to be normal for humans to increase the number of mental classifications and subdivisions as the individual learns more knowledge, regardless of whether the knowledge is correct or incorrect. A parallel is the tendency for individuals with highly scored IQs to use words that are more complex than average. More than once I have observed individuals with average IQ scores complain about the complexity and quantity of the high IQ person's choice of words, with the average IQ person claiming that the high IQ person could have conveyed the same information with a low quantity of small words. The average IQ individuals did not realize that the high IQ individuals actually do think abstract thoughts that are as complex — or more so — than the words chosen, and that within the choices of words there existed depths of definitions that point to complexities of topics that cannot be communicated with only a few small words. However, similar to the electricity example, an individual of tremendous conscious awareness (i.e. Buddhist enlightenment) and experience may use a very few number of words, with the words pointing to concepts that can only be comprehended if the listener has experienced a similar awareness. The point here is that the ability to create numerous mental classifications and subdivisions is often a gauge of a higher developed mind, although not always.

Another common ability among humans is to create and comprehend metaphors. Most adults readily comprehend what is meant by "shot out of the house" and "plant a good seed". An observable difficulty with the ability to understand metaphors is that some individuals do not appear to know when to stop. "Planting a good seed" might be interpreted to imply "begin with good knowledge", but the conclusion is then given a metaphorical interpretation itself, and with each following conclusion also being given a metaphorical interpretation. The oddity appears to be most common within the writings of religions and philosophies, but perhaps the reason is because it is usually only within religions and philosophies that metaphors are commonly used.

Between the normal human abilities of creating mental classifications and metaphors, it is not uncommon for humans to create mental classifications that are metaphorical to one another, and the quantity and complexity of the metaphorical classifications are often proportional to the individual's intellectual potential. It is very common for people to know a lot of knowledge, and yet the knowledge might simply be invented abstracts that pertain to nothing real. All humans suffer from the same malady, and no one is fully immune.

Two things useful of noting here are: (1) just because a person has knowledge of many classifications, it does not necessitate that the knowledge is true, (2) and sometimes, as in the awareness and electrical classification examples, excessive classifications may suggest a lack of understanding of the thing that is being classified. In general, popular philosophies surrounding the topic of ethics are built upon the act of repetitiously classifying sub-categories of classifications, and then inventing metaphorical knowledge to place within the sub-categories. Most people use the words "ethical", "moral", and "right" synonymously, as do they use "unethical", "immoral", and wrong" synonymously, and yet it is well-known that there does not exist within the public a well-defined knowledge of what is right and wrong, and so therefore it is also known that the classifications within the philosophical concept of ethics will likely contain invented metaphors.

Applied Ethics is a subgroup of the classification of philosophical ethics, and the knowledge within the practice of Applied Ethics may be more metaphorical than fact, and if so, then it required a substantial quantity of intelligence to invent the philosophical view. The ideal at this point would be for the same intelligence to choose to investigate the origins of right and wrong, not within metaphors, but within what is real. The following paragraphs will hopefully help to illustrate where the investigation ought to begin: within each individual, and with awareness.

An example of Applied Ethics, and allegedly a true story, is of a CEO of a large corporation who was well-known for his high moral standards. When an opportunity arose for the company to open a new branch in a foreign country where the company expected to earn about $100,000,000.00 per year, there were four ethical problems: (1) It was customary and required that the company bribe the country's local officials for permits, (2) the company had to sign a legal document stating that it had not bribed anyone to attain the permits, (3) it was possible for the company to pay middlemen to do the bribing while the company pretended to not know that bribes were taking place, and (4) the CEO might lose his job if he did not get a branch opened in the foreign country.

There was no 'ethical' problem in the scenario, there was only a problem of deciding whether the weight of money outweighed the risk of jail, and whether the desire for money was more important than one's honor and word. This particular case well-illustrates that the common usage of "ethics" and "morals" has nothing to do with right and wrong, but rather the concept of ethics is merely the weighing of pre-established preferences. Each individual already has pre-established weights of chosen standards, and as long as one desirable thing does not outweigh the standards of another desirable thing, then the person will continue to behave under whichever self-chosen standard appears to serve best at the moment. As an example, an individual may have a standard of desiring honesty so as to attain social acceptance, a standard of desiring money, and a standard of desiring prestige. If the quantity of money and prestige are not too great, then the person will remain being honest, but if sufficient money and/or prestige is made available, then they will outweigh the standard of honesty, and the individual will with logic weigh that the money and/or prestige are more important than honesty and social acceptance.

Would you kill someone for a dime? And if not, then why not? Would you kill someone for ten dollars, and if not, then why not? Would you kill someone for $100,000,000.00, and if yes, then why? You see, for most people, each person's system of standards is flexible, and most humans will quickly steal and murder if the weight of a desirable thing outweighs the weight of the person's other standards. As the Milgram experiment brightly illustrated, about 60-80% of all humans will murder another human if told to do so by an authority figure. With the only reward being that of being accepted by authority, most people have a standard that is heavily weighted with the desire to obey authority.

Generally, the thing named "ethics" in Applied Ethics is not 'ethics' at all, but rather only a logic-based set of desires and beliefs. There is, of course, a much deeper causation, but what has been said should already be enough for an individual to recognize that right and wrong in scenarios are not in the choosing of whether to bribe or murder, but rather right and wrong are logically-derived choices that had already been decided and established long before a person makes a choice within a scenario. All that a scenario does is to make it possible for the person's true inward self to be made known. I will repeat it again: all that a scenario does is to make it possible for the person's true inward self to be made known. Any right and wrong that may exist will have already existed within the individual's foundation of logic.

To better clarify the above paragraph, and to draw from what is real in Reality; creativity is the nature of the Universe, that nothing can come into existence without there first being the nature that enables creativity to exist. The standard and origins of creativity do not exist in the created thing (the created thing did not create itself from nothing), but rather the act of creativity has for itself a nature — a standard — that enables things to be created. That which is created, is an illustration of what is possible within the nature of the thing that created the Universe. The nature and standard of creativity are the origins of Creation, with Creation being as the scenario that makes it possible for the nature of creativity to be made known to the observer. Similarly, a person does not choose his/her own nature during a scenario, but rather the inward nature already existed prior to the scenario, and all that the scenario does is to be a situation where an observer can observe how an individual's nature will react to different circumstances.

Any judgment that may occur during a scenario will be based upon the individual's pre-established standards, and though a number of the person's standards might change during a scenario, the change of standards will themselves still remain judged on preexisting standards. As an example, within a scenario of an individual acquiring a sales job, the individual may have always been honest in the past, but within the scenario the person chooses to become dishonest. The hypothetical preexisting standards were those of choosing honesty and providing necessities for life for the person's family. If the scenario included an economic depression plus an aggressive sales manager (authority), the individual's preexisting standard may choose to follow what is held to be the most important, which would be life, and the person would choose dishonesty so as to retain the job. All choices are influenced by pre-established foundational choices, whether the choices be of an inwardly or an outwardly focus, and the string of self-chosen standards are easily observed to have been the logical choices that are in agreement with the foundational standards. (Natural Laws helps to explain more within a Platonic style of dialogue.)

Common modern scientific thought is that the nature of a thing can be known if it is dissected and its parts are measured. Individuals with a knowledge of Nature know that the destruction of a thing will produce no useful knowledge beyond the mathematical numbers of the thing's external form, but, however, useful knowledge of a thing's nature can be observed when two or more things are placed in close proximity and then watched to see how the things react to the other. (The article Type A and B Intelligence provides further information.) The same method is used to observe the inward nature of all living creatures, and it is within scenarios that the inward natures will be observed. The concept of right and wrong might better be replaced with a concept of what is creative and destructive, which would then be in parallel to the only permanently fixed and unmovable triangulation point in the Universe: the natural laws of Nature.

Applied Ethics is useful to illustrate through scenarios how self-chosen desires react in the real world, but Applied Ethics most assuredly has no potential for discovering right and wrong.

Part Two

In the question of asking what is right behavior and what is wrong behavior, western philosophy approaches the topic through a dialogue that does not first have a standard to measure right and wrong. If the topic asked if it were right or wrong that rocks fall to the ground, then the answers would rely on the firsthand observations of watching rocks fall to the ground, and thus the known laws of Nature — laws that no man nor creature can disobey — would become the judge of what is right and what is wrong. If the questions were of the topics of astronomy, chemistry, or biology, then again the answers would be judged by the known laws of Nature (physics), but rarely are the laws of Nature taken into consideration within western philosophy's question of human behavior.

Observe, that in western philosophy's sequencing of logic there first exists the question of what is right and what is wrong, with the answer to what is right and wrong being an unknown. Without knowing the answer to what is right and wrong, western philosophy speaks of a scenario of human events — whether the scenario is real or imaginary — and then western philosophy attempts to find what might be right or wrong within the scenario.

It is not possible for any man to judge a thing right or wrong without the man first knowing what is right and wrong. Similar to the circular dictionary definitions of "ethics are moral standards" and "morals are ethical standards", western philosophy's logic is circular in that it believes it can discover an unknown (right and wrong) within another unknown (scenario), and then, it is believed, the decision of what is right or wrong in the scenario will define the words right and wrong. Roughly phrased to illustrate a similarity to the circular dictionary definition of ethics, western philosophy believes "the decision of what is right is found within scenarios" and "the decisions of scenarios are judged by what is right". The reasoning is circular, it begins nowhere, and it ends nowhere.

As the dialogue of Firsts discusses, proper logic requires a proper sequencing of events, with each accurate conclusion being built upon an accurate previous conclusion. The Universe and all the laws of the Universe existed first, man did not exist before the Universe, nor before the laws, and thus it is logical to conclude that the created thing (man) cannot create laws that rule over the creator (Universe). An event or scenario is never the creator of actions and laws, and never will the created thing become the law of that which created the thing. Right and wrong existed before man and man's scenarios, and never will man nor his scenarios — the created things — become the creators of a thing that existed before man.

Correct logic dictates that it is necessary for the definition of a thing to be known before the thing can be measured. If a question asks how may atoms might exist in a molecule, then it is logical to first know what an atom is, what a molecule is, and what the measurements are of atoms and molecules. It is not sensible for any man to believe that he can count the number of atoms in a molecule without the man first knowing what an atom is, and yet some philosophies commit a similar fallacy of logic when attempting to count right and wrong within scenarios.

Within the scenario of the public debating abortion, one side of the debate claims that abortion is right because abortion helps to slow the problem of over-population, because a woman has the human right to do with her body as she pleases, and because abortion is legal. On another side of the debate are the claims that abortion is wrong because the unborn child is conscious, because the person's religion forbids it, because the fetus is a separate human being, and because abortion is illegal. All of the arguments may have some validity, but from each valid statement can be drawn a difference of conclusion. Can a correct conclusion of right and wrong be decided from an argument if all arguments are based on correct information, but the person merely picks and chooses bits of data that support the individual's preexisting belief and bias?

In the above example of abortion the reasons for the choices were already in existence, that the individual had already formed a conclusion of what the individual wants, and the individual then picked and chose which of the facts that might best support the preexisting choice. The scenario of debating abortion does not have within it a possibility of discovering right and wrong within the debate, but rather the answer to right and wrong must be looked for in the reasoning of why the individuals had formed the preexisting choices. A person favoring abortion may have formed the choice because the person does not want children — for whatever reason — and the person now wants to be socially excused from having more children. The choices for and against abortion are in most all instances already in place, and if a choice is to be weighed right or wrong, then the judgment should be of the preexisting decisions and not of a scenario.

Also notice that the above two paragraphs are — in a manner — invented scenarios. There was no talk of physics, no talk of biology, no discussion about the psychological structuring of the mind, no talk of how personal experiences influence a person's logic, and the majority of the wordage was generally of no value except to illustrate that wordage without substantiating facts is just wordage. It is common for humans to debate scenarios — some of the debates have continued for over three-thousand years — but the debates would be quickly ended if the reasoning behind the topics were to be explored.

A person might say that if right and wrong are not found within scenarios, and that the choices for behaviors were in existence prior to the behaviors themselves, then that would imply that the search for right and wrong must then reside within the realm of psychology, not philosophy, and if the thought were carried further, it would then be found that the answers for right and wrong would be dictated by physics, not psychology. Such a view, that the origins of right and wrong might be found in physics, is a good place to start.

Applied Ethics is given the description that it is a classification of philosophical inquiry that attempts to find what is right and what is wrong in scenarios such as the abortion topic. Nevertheless, as it is repeatedly asked, how can a thing be judged right or wrong in a scenario if right and wrong are not known beforehand?

As a classification within philosophy, Applied Ethics has the usefulness of being a topic for young minds to exercise their reasoning and to gain abstract thoughts of life, but Applied Ethics itself has numerous flaws in its logic, primarily those of beginning without a standard of right and wrong, of not knowing the definition of right and wrong, of attempting to find right and wrong in scenarios, of attempting to define right and wrong from scenarios, and of each conclusion being contradicted by all other conclusions.